Population growth and the construction boom of the Gründerzeit period created an enormous demand for designers of interior furnishings and everyday objects. To train them, new arts and crafts schools were founded throughout Europe from the 1860s onwards, modeled on the English design schools. The first of its kind was the Arts and Crafts School (Kunstgewerbeschule) of the Imperial-Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry in Vienna (founded in 1867, today the Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien).

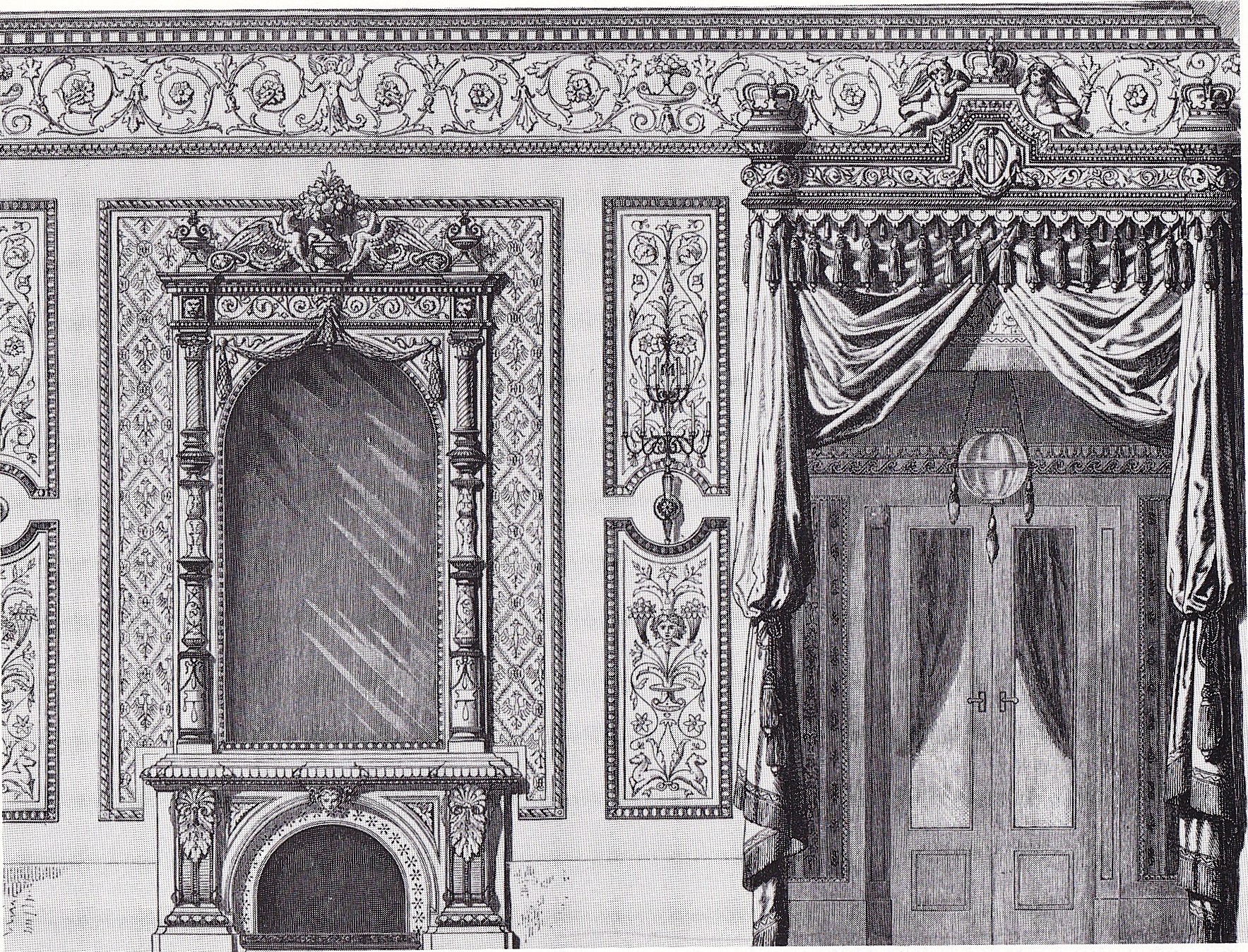

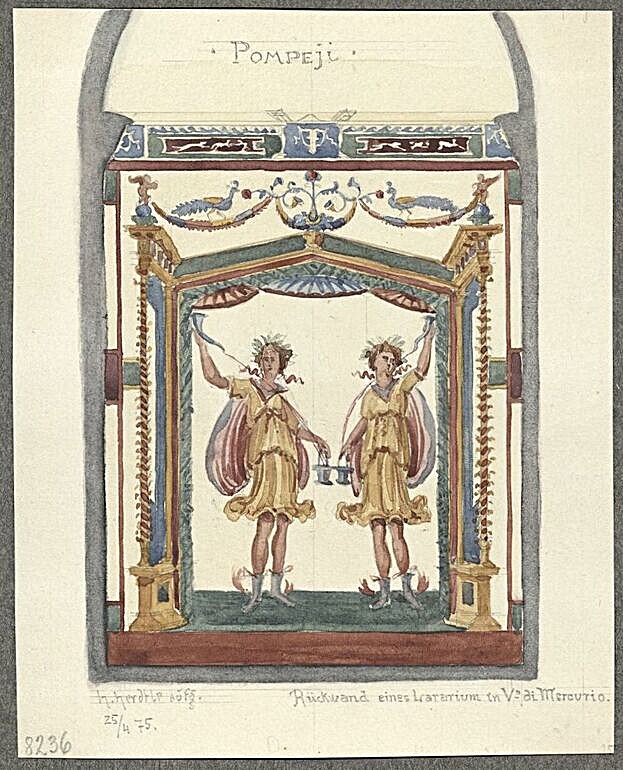

Here, specialists in ornamentation and furniture design began to train the new professionals in interior design and product design in three „specialist classes for architecture“. Professors Josef von Storck, Hermann Herdtle, and Oskar Beyer shaped the historicist design of the Ringstrasse era in the Neo-Renaissance style from the founding of the Kunstgewerbeschule to the beginning of modernism around 1900.

1867: Timetable for the architecture classes

– Daily 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Specialized class

– Four times a week in the evening: Drawing from a live model

– Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday from 3:30 to 4:30 p.m.: Lectures on projection, shadow theory, and perspective

– Monday and Saturday 5-6 p.m.: Lectures on style and terminology

– Monday and Saturday 7-8 p.m.: Lectures on color chemistry

Josef von Storck

(Vienna, April 22, 1830 – March 27, 1902, Vienna)

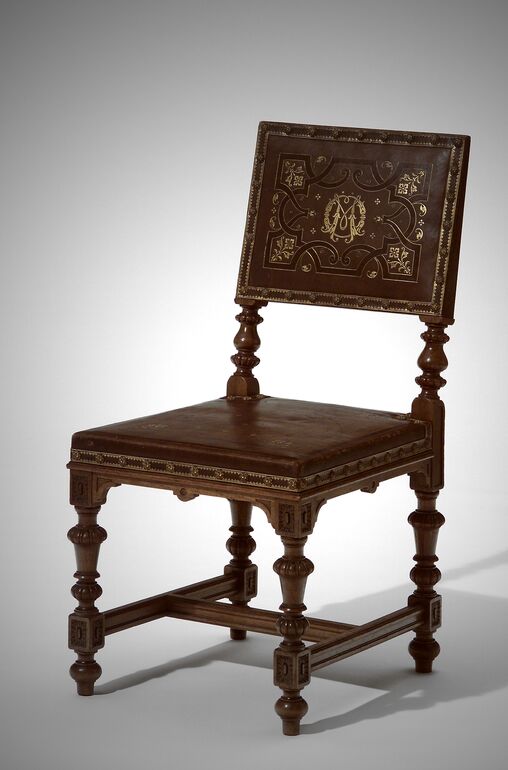

Son of a Viennese watchmaker, studied architecture at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts under Eduard van der Nüll from 1847, worked in van der Nüll’s private studio (designs for the interior decoration of the Court Opera from 1860), drawing teacher at the manufacturing drawing school of the Lower Austrian Trade Association, from 1862 teacher of ornamental drawing at the Vienna Academy, 1866–1877 for ornamentation and ornamental drawing at the Polytechnic Institute in Vienna, collaborated on the Museum of Military History in Vienna (from 1865) and on buildings for the Vienna World’s Fair in 1873, numerous designs for manufacturers such as J. & L. Lobmeyr and Philipp Haas & Söhne as well as for the series „Kunstgewerbliche Vorlage-Blätter“ (Artistic Craft Templates), founding director and professor of architecture at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts 1867–1902.

Secession propagandist Ludwig Hevesi about Josef von Storck, 1899

„When (museum director Rudolf von) Eitelberger set out to revive the dying arts and crafts industry, he did not have a wide selection of employees to choose from.

He took on writers and illustrators, regardless of their quality. Storck was a fresh, energetic character and had a knack for getting along with people. However, van der Nüll was quite disappointed when he saw his work for the court opera, where Gugitz completely overshadowed him. He was the ‘doer’ who could be relied upon under all circumstances. He became director of the School of Arts and Crafts, and even professor of architecture there, although it is well known to all involved that he did not like to ‘meddle in architectural matters’ but sought Herdtle’s advice on such matters.“

Hermann Herdtle

(Stuttgart, July 2, 1848 – September 7, 1926, presumably Vienna)

Son and pupil of the Württemberg painter of the same name, studied at the Polytechnic in Stuttgart from 1866 to 1870 under Wilhelm Bäumer, worked at the Bäumer studio from 1870 to 1873 on the planning of the Northwest Station in Vienna.

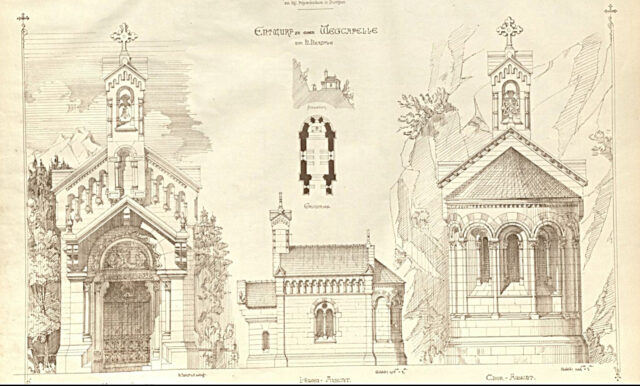

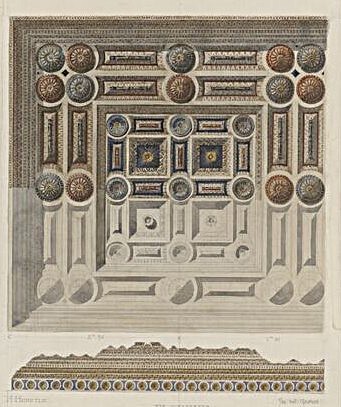

Study trip to Italy in 1874/75, 1876–1913 teacher and head of a specialist class for architecture at the Vienna Kunstgewerbeschule, editor of numerous reference works such as „Mustergiltige Vorlageblätter zum Studium des Flach-Ornaments der italienischen Renaissance, Original-Aufnahmen in natürlicher Größe dargestellt“ (Stuttgart 1884)

and „Ostasiatische Bronze-Gefässe und Geräthe in Umrissen, ein Beitrag zur Gefässlehre. Zum Studium und zur Nachbildung für Kunstindustrie und gewerbliche Lehranstalten“ (East Asian bronze vessels and utensils in outline, a contribution to the study of vessels for study and reproduction for the arts and crafts industry and commercial educational institutions, Vienna 1883).

Allgemeine Kunst-Chronik, July 4, 1884, p. 533

(…) Today we have the pleasant duty of announcing a new publication by Herdtle, which testifies to both his refined taste and his sure teaching instinct, namely his collection of Italian majolica tiles. The 26 plates in the collection are not compilations from other works, but original drawings from two Genoese palaces in which the walls of the stairwells are covered with majolica tiles like a carpet, partly based on Spanish-Moorish patterns, whose tradition is still not completely extinct on the Iberian Peninsula today.

The author rightly points out how well these surface decorations, with their strictly geometric arrangement and consistently vegetal ornamentation – incidentally, a sure sign of Spanish-Moorish origin – correspond to the stylistic laws of cladding, which has its model in carpets.

This new publication is primarily intended to serve the purposes of art education by offering schools simple models for surface ornamentation, instead of the excessive waste of color in the garishest combinations that otherwise prevails in this field in the early grades of art education. The harmonious color combinations of ceramics, favored by the limited palette, can only do good here.

Secondly, this publication also provides the modern tile industry, which has regained prominence in the decoration of our homes, with good examples worth emulating. Herdtle’s work is therefore highly recommended for commercial schools and institutions.“

(Review of:) Vorlagen für das polychrome Flächenornament. Eine Sammlung italienischer Majolika-Fliesen, Aufgenommen und herausgegeben von H. Herdtle, Architekt und Professor an der Kunstgewerbeschule des k. k. österreichischen Museums (Wien, C. Graeser) – (Templates for polychrome surface ornamentation. A collection of Italian majolica tiles)

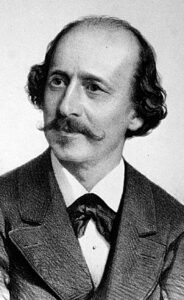

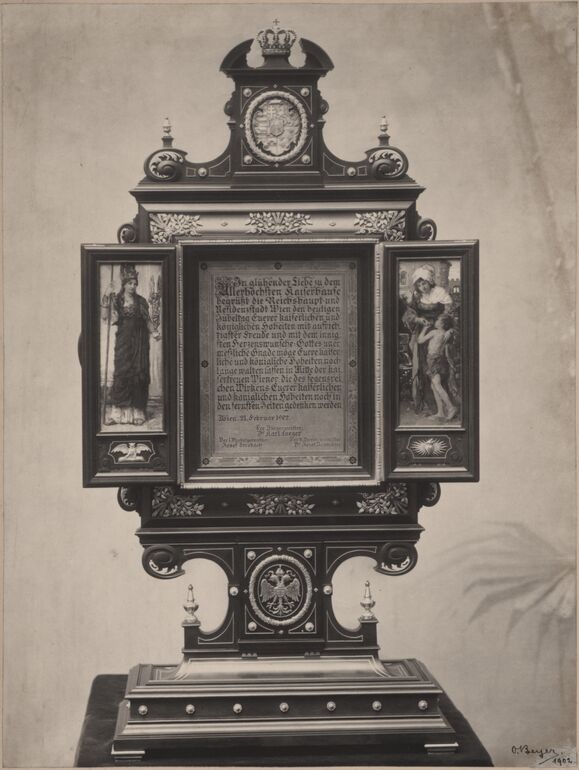

Oskar Beyer

(Dresden, February 23, 1849 – March 22, 1916, Vienna)

studied 1868–71 at the Vienna Kunstgewerbeschule under Josef von Storck, worked 1871–73 in the construction and decoration office of the World Fair in Vienna, 1878–1906 Professor and head of a specialist class for architecture at the Kunstgewerbeschule, editor of the template series „Die Nadelschrift“, 1905–06 and 1908–09 Director of the Kunstgewerbeschule.

Adalbert Franz Seligmann, Exhibition of the School of Applied Arts of the Austrian Museum. In: Neue Freie Presse, June 10, 1906, pp. 13/14

(…) For some time now, it has been noticeable that the relationship between arts and crafts schools and academies is undergoing a change comparable to that experienced by polytechnic schools in relation to universities. Academies and universities are subject to multiple attacks; their statutes and institutions are considered outdated and no longer in keeping with the times. (…) Polytechnics have become institutions of higher education that are virtually on a par with universities, which is most clearly demonstrated, among other things, by their right to award doctoral degrees. And even if the arts and crafts schools, which cannot claim a higher level of education from all their students, do not appear to be on a par with the academies from the outside, they have in fact already surpassed them in importance. In modern arts and crafts schools, students learn everything they learn at the academy, plus a lot of other highly important things that are not taught at art colleges at all, or are taught according to outdated principles and in a rather imperfect way. (…)

The way in which Moser’s and Mallina‘s departments familiarize students with all kinds of techniques is certainly of great benefit, even if, perhaps, these schools in particular occasionally achieve somewhat peculiar results due to an excess of variety on the one hand and material-based stylization and simplification on the other. (…) In general, a recent moderation is perhaps the most characteristic feature of this very modern art school. Even in Jos. Hoffmann’s department, we no longer find furniture, everyday objects, and interior decorations in the sharpest tones – except for architecture. (…) Suffice it to say here that, just as in earlier stylistic periods architecture influenced the arts and crafts, so that cabinets, furniture, and appliances were decorated with ornamentation borrowed from grand architecture, now, conversely, the arts and crafts dictate the forms—and sometimes the formlessness—of architecture. Whereas previously a sideboard or a grandfather clock might have been decorated with miniature versions of a temple façade or a portico, houses are now being built in the shape of boxes, caskets, and the like. However much good the modern movement may have done in the arts and crafts, it has certainly done a great deal of damage in architecture. (…)

Oskar Beyer, Letter to A. F. Seligmann, 13. June 1906, Vienna Library in City Hall, Manuscript Collection, Inv. No. 35.192

Your Excellency, Dear Sir!

Your review of the exhibition of student works from the School of Applied Arts at the Austrian Museum, which appeared in the Neue Freie Presse on the 10th of this month, stands out in a distinguished and refreshing manner from a whole series of reviews of the exhibition in the Viennese daily newspapers. The undersigned director therefore considers it its duty to express its gratitude to you, esteemed sir.

As an artist and teacher with professional experience, you approached the institution without bias, which allowed you to be completely objective both in general and in detail, without overlooking any weaknesses that may exist.

In particular, the school was pleased that your essay refrained from the kind of bombastic praise of young talent that has led many a student astray, to premature arrogance.

Please accept, dear Sir, our expression of special esteem on this occasion, but also our request that you continue to show not only your goodwill toward the institution, but also your complete objectivity.

Yours sincerely,

School of Applied Arts of the Imperial and Royal

Austrian Museum of Art and Industry

Director:

Oskar Beyer